If The Lungs Would Be Opened Out And Laid Flat, What Size Area Would They Cover?

- Enquiry article

- Open Admission

- Published:

The effect of body position on pulmonary function: a systematic review

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 18, Commodity number:159 (2018) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are routinely performed in the upright position due to measurement devices and patient comfort. This systematic review investigated the influence of torso position on lung part in salubrious persons and specific patient groups.

Methods

A search to identify English-language papers published from one/1998–12/2017 was conducted using MEDLINE and Google Scholar with central words: trunk position, lung role, lung mechanics, lung volume, position modify, positioning, posture, pulmonary office testing, sitting, continuing, supine, ventilation, and ventilatory modify. Studies that were quasi-experimental, pre-mail service intervention; compared ≥2 positions, including sitting or standing; and assessed lung function in not-mechanically ventilated subjects aged ≥18 years were included. Master consequence measures were forced expiratory volume in ane s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC, FEV1/FVC), vital capacity (VC), functional residuum capacity (FRC), maximal expiratory pressure (PEmax), maximal inspiratory pressure (PImax), peak expiratory flow (PEF), total lung capacity (TLC), balance volume (RV), and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Continuing, sitting, supine, and right- and left-side lying positions were studied.

Results

Forty-three studies met inclusion criteria. The written report populations included healthy subjects (29 studies), lung disease (9), heart disease (four), spinal cord injury (SCI, seven), neuromuscular diseases (three), and obesity (four). In nearly studies involving healthy subjects or patients with lung, heart, neuromuscular affliction, or obesity, FEV1, FVC, FRC, PEmax, PImax, and/or PEF values were higher in more cock positions. For subjects with tetraplegic SCI, FVC and FEV1 were higher in supine vs. sitting. In salubrious subjects, DLCO was higher in the supine vs. sitting, and in sitting vs. side-lying positions. In patients with chronic heart failure, the upshot of position on DLCO varied.

Conclusions

Body position influences the results of PFTs, just the optimal position and magnitude of the benefit varies between study populations. PFTs are routinely performed in the sitting position. We recommend the supine position should be considered in improver to sitting for PFTs in patients with SCI and neuromuscular illness. When treating patients with center, lung, SCI, neuromuscular disease, or obesity, one should take into consideration that pulmonary physiology and function are influenced by torso position.

Background

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) provide objective, quantifiable measures of lung function. They are used to evaluate and monitor diseases that affect heart and lung function, to monitor the effects of environmental, occupational, and drug exposures, to assess risks of surgery, and to assistance in evaluations performed earlier employment or for insurance purposes. Spirometric examination is the most mutual class of PFT [i]. According to ATS/ERS guidelines, PFTs may be performed either in the sitting or standing position, and the position should be recorded on the written report. Sitting is preferable for safety reasons to avoid falling due to syncope [ii], and might also be more convenient because of the measurement devices and patient comfort. However, people who suffer from neuromuscular disease, morbid obesity, and other conditions may find information technology difficult to sit or stand during this test, which may influence their results.

Ane of the chief goals of positioning, and specifically the employ of upright positions, is to better lung function in patients with respiratory disorders, eye failure, neuromuscular disease, spinal cord injury (SCI), and obesity, and in the past twenty years, diverse studies regarding the influence of trunk position on respiratory mechanics and/or function have been published. Withal, we did non observe a systematic review that integrates findings from studies involving not-mechanically ventilated adults to derive clinical implications for respiratory care and pulmonary function examination (PFT) execution.

We aimed to systematically review studies that evaluated the effect of torso position on lung function in healthy subjects and non-mechanically ventilated patients with lung disease, heart disease, SCI, neuromuscular disease, and obesity.

Methods

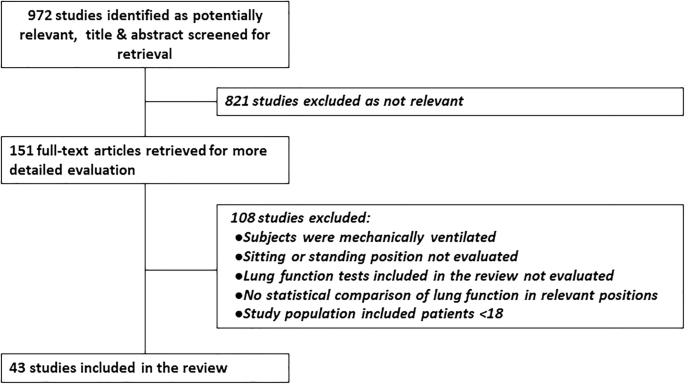

Ii researchers (SK., E-LM.) searched MEDLINE and Google Scholar for studies published from January 1998–December 2017 using the key words torso position, lung function, lung mechanics, lung volumes, position change, positioning, posture, PFTs, sitting, standing, supine, ventilation, and ventilatory change, in various combinations. Each search term combination included at to the lowest degree 1 primal word related to pulmonary function and at least 1 related to body position. The twelvemonth 1998 was called every bit the outset signal due to the publication of the seminal study by Meysman and Vincken [three]. A full of 972 abstracts identified in the search were screened by the aforementioned two researchers, and total text of 151 potentially relevant articles was obtained. The full texts were evaluated and categorized, and 108 articles not fulfilling the inclusion criteria were excluded (Fig. ane).

Study menstruation diagram

Manufactures were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Quasi-experimental, pre-postal service intervention. (2) Ii or more body positions compared, including at to the lowest degree the sitting or standing position. (3) Event measures included assessment of lung office by forced vital chapters (FVC), forced expiratory book in 1 s (FEV1), FEV1/FVC, vital capacity (VC), functional residual capacity (FRC), maximal expiratory pressure (PEmax), maximal inspiratory pressure (PImax), peak expiratory menstruation (PEF), total lung capacity (TLC), residual book (RV), or diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). (4) Study population of not-mechanically ventilated subjects. (5) Participants aged ≥xviii years. (vi) English language. Studies assessing lung part using other criteria and those without statistical comparisons of lung function in dissimilar positions, those enrolling individuals < 18 years or on mechanical ventilation, published briefing abstracts, and systematic reviews were excluded.

Positions studied

- ane.

Standing – unsupported active standing

- 2.

Sitting – sitting on a chair or wheelchair with the backrest at 90° and all limbs supported

- 3.

Supine – lying flat on the dorsum

- 4.

Right-side lying (RSL) – lying direct on the correct side

- five.

Left-side lying (LSL) – lying straight on the left side

Outcome measures and defined thresholds for clinical significance

- 1.

FVC – forced vital chapters

-

Change of 200 ml or 12% from baseline values in FVC [4]

-

- 2.

FEV1– forced expiratory volume in 1 s

-

Modify of 200 ml or 12% from baseline values in FEV1 [4]

-

- 3.

FEV1/FVC – forced expiratory book in 1 s divided by forced vital capacity

-

FEV1/FVC < 0.7 is defined as obstructive disease

-

- iv.

VC – vital capacity

- 5.

FRC – functional rest capacity

-

Modify > ten% [5]

-

- half dozen.

TLC – total lung capacity

-

Change > 10% [5]

-

- seven.

RV – residual volume

- 8.

Maximal expiratory pressure (PEmax)

-

Change ≥24 cmH2O [6,7,8]

-

- ix.

Maximal inspiratory force per unit area (PImax)

-

Change ≤ − thirteen cmH2O [vi,7,eight]

-

- ten.

Peak expiratory catamenia (PEF)

-

Change > 10% or lx 50/min [9, 10]

-

- 11.

Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO)

-

Change ≥10% in DLCO [11, 12]

-

2 experienced pulmonologists (NA, AR) reviewed the included studies in consensus to identify statistically significant and clinically important differences in pulmonary function. Results from articles included in the review were evaluated by all authors and categorized by study population, torso positions studied, and outcome measures. Data from included studies was extracted by iv authors (NA, AR, SK, East-LM.) independently and in consultation when questions arose. The review was performed co-ordinate to the PRISMA guidelines [13].

Although these are not interventional studies, strictly speaking, we have called to assess them every bit "before and after intervention," wherein the posture/position change is the maneuver of interest. Level of testify was assessed according to the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Classification of Evidence for therapeutic intervention [xiv]. Hazard of bias was assessed according to the Quality Cess Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Command Group developed by the National Centre, Lung and Claret Institute (NHLBI) of the US National Institutes of Wellness (NIH) [15]. This tool is comprised of 12 questions assessing various aspects of the quality of the report. 2 authors (Eastward-LM, SK) independently scored each report using the technique from Kunstler et al. [16]. Differences were resolved in consensus, in consultation with a third author (YZ). The gamble of bias was categorized as depression (score 76–100%), moderate (26–75%) or high (0–25%).

Results

Studies included in the review

A full of 43 studies fully met inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Fig. ane). All studies used either consecutive, convenience, or volunteer sampling to enroll healthy individuals or subjects with various medical atmospheric condition. All studies provide Class Iii level of testify.

The protocols and level of bias in the various studies are shown in Table ane and Additional file i: Table S1. Risk of bias was assessed as moderate in 41 studies and low in two. Quality problems were primarily related to sampling techniques for enrolling study participants. All studies used non-random sampling. Some studies investigating healthy subjects included convenience samples of immature participants, mainly students. Only 7/43 studies reported sample size calculations required to reach statistical power. In addition, the details of the intervention protocol were not clearly reported in some studies (Table i) and due to the nature of the written report assessors could not be blinded to patient position or outcomes from previous tests.

A summary of study characteristics, including the positions studied, outcome measures, and main results according to the report population, is shown in Table 2. Out of 43 studies, 29 included healthy subjects, 9 included patients with lung disease, four included patients with center disease, seven included patients with SCI, three included patients with neuromuscular diseases, and iv included patients with obesity. Additional file 2: Table S2 summarizes only the statistically significant findings for each relevant issue variable, according to position, for each of the populations studied.

FVC

The association between FVC and body position in healthy subjects was investigated in thirteen studies [3, 17,18,xix,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. There was a clinical and statistically significant increment in FVC in sitting vs. supine positions [three, eighteen, 22,23,24,25,26,27], in sitting vs. RSL and LSL [3, 21], standing vs. supine [19, 23], and standing vs. RSL and LSL [nineteen]. In a smaller number of studies there was no modify between continuing and sitting [nineteen], sitting and supine [17, 21, 28] or sitting and RSL or LSL [21], and one written report [22] found a decrease in FVC from sitting to continuing that was statistically but not clinically meaning. Thus, in the majority of studies the more upright position was associated with increased FVC.

Four studies included subjects with lung affliction [29,30,31,32]. Among asthmatic patients in one study FVC increased significantly from supine to standing [30]; withal, in that location was no significant departure betwixt standing and sitting or betwixt sitting and supine, RSL, or LSL. Another written report reported a statistically and clinically pregnant increase in FVC in standing vs. sitting, supine, RSL, and LSL and in sitting vs. supine, RSL and LSL [31]. Among obese asthmatic patients [32], and among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [29], no difference was found in FVC between standing and sitting.

Three studies included subjects with congestive middle failure (CHF) [18, 21, 27]. In ane study, FVC was reported 200 ml higher in sitting vs. RSL and LSL [21], and in the other ii studies FVC was college in sitting vs. supine by 350–400 ml, which has clinical significance [eighteen, 27].

Six studies included patients with SCI [17, 33,34,35,36,37]. The effect of body position on FVC depends on the level and extent of injury. Amongst those with cervical SCI, FVC was college in the supine vs. sitting position [17, 33, 34]. Other studies [35,36,37] did not find significant differences in FVC for patients with SCI in a pooled group of all levels of injury for these positions. All the same, in patients with cervical SCI, likewise as those with thoracic injury in one study [36], there was an increased FVC in the supine vs. sitting, while in those with thoracic or lumbar injury FVC was college in the sitting position [37]. The differences did not always reach statistical significance. Nevertheless, information technology is important to note that in these debilitated patients with SCI, even a pocket-size change in FVC is probably clinically pregnant.

Three studies evaluated patients with neuromuscular diseases [25, 34, 38]. In patients with myotonic dystrophy and in those with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), in that location was a clinically and statistically significant decrease in FVC from sitting to supine [25, 34, 38]. In subjects with obesity (mean BMI 36.seven) no pregnant departure was reported between standing and sitting [32].

FEV1

In salubrious subjects, FEV1 was reported to be college in sitting vs. supine [iii, eighteen, 22, 23, 26, 27, 39], in sitting vs. RSL and LSL [3, 19, 20], in standing vs. sitting [23], and in continuing vs. sitting, supine, RSL, and LSL [nineteen]. However, other studies [21, 24, 28, 40] did not detect significant difference for FEV1 between sitting and supine, RSL, and LSL. One study [22] reported a decrease of 120 ml in FEV1 from sitting to standing, which is statistically but not clinically meaning.

Among asthmatic patients, FEV1 was higher in the standing vs. supine position, a statistically and clinically significant modify; however, there was no significant difference between sitting vs. supine, RSL, and LSL positions [xxx]. Another written report in asthmatic patients reported FEV1 to be higher in standing vs. sitting, supine, RSL, and LSL, and in sitting vs. supine, RSL and LSL [31]. Amidst obese asthmatic patients and those with COPD, there was no significant difference in FEV1 betwixt standing and sitting [29, 32].

In subjects with CHF, one written report found a statistically and clinically significant increase in FEV1 in sitting vs. RSL and LSL, just no difference between sitting and supine [21], while two other studies reported higher FEV1 in sitting vs. supine [18, 27].

In patients with SCI, FEV1 was recently reported to increase from sitting to supine [twoscore]; however, other studies institute that the effect of position on FEV1 in those with SCI depends on the level and extent of injury. In i study amid all subjects with SCI, FEV1 was not significantly influenced by moving from sitting to supine [35], but patients with cervical injuries showed a tendency for increased FEV1 in the supine vs. sitting position while those with thoracic injuries tended towards increased FEV1 in the sitting position. Along the same vein, another study [36] found an increase is FEV1 in the sitting vs. the supine position in patients with lumbar injury while FEV1 was college in the supine position for those with cervical spine or thoracic injuries. Although the differences between positions were not statistically significant, the issue of level of injury was statistically and clinically meaning.

In another study [33], FEV1 was higher in supine vs. sitting in patients with complete tetraplegia, while in patients with incomplete injury there was no significant difference between positions. Another group [37] reported no pregnant change in FEV1 between the sitting and supine positions for a pooled group of patients with SCI, only in the subgroup of patients with incomplete motor injury and in those with incomplete thoracic motor injury there was a decrease in the supine position.

In patients with myotonic dystrophy, FEV1 decreased from sitting to supine [38]. Among those with obesity, FEV1 was college in sitting vs. supine both before and later on bariatric surgery [41]. In another written report amid obese patients, there was no difference in FEV1 between standing and sitting [32].

FEV1/FVC

Seven studies compared FEV1/FVC for dissimilar body positions in good for you subjects [eighteen, 19, 23, 24, 27, 28, 42]. In several studies, FEV1/FVC was reported to be college in sitting vs. supine [23, 28], in sitting vs. LSL [19], and in standing vs. supine, RSL, and LSL [19]; still, FEV1/FVC was > 70% in all body positions so the difference was not clinically meaning. Other studies found no difference between sitting and supine [18, 24, 27] or standing, sitting, and supine [42].

Among subjects with asthma, CHF, and obesity no statistically significant departure in FEV1/FVC was constitute between the different body postures [18, 27, 32, 42].

Vital capacity

The effect of body position on vital chapters was evaluated in vi studies of healthy subjects [21, 24, 28, 39, 43, 44]. In almost studies no divergence was reported between sitting and supine [21, 24, 28, 43] or betwixt sitting and RSL or LSL [21]. One report [39] constitute that VC was higher in the sitting vs. supine position. However, another written report [44] found that VC was higher in the supine vs. sitting position, but only in females.

In patients with CHF, VC was reported to be higher in sitting vs. supine in one study [27] while another study found no statistically pregnant departure between these positions [21]. In patients with spinal cord injury, VC was higher in the supine vs. sitting position [40]. In subjects with obesity, no difference in VC was reported betwixt the sitting and supine positions [41, 43].

PEF

PEF in different body positions was evaluated in 13 studies [iii, 22,23,24, 31, 33, 45,46,47,48,49,l,51]. 8 studies evaluated but healthy adults [3, 22,23,24, 45, 48, 50, 51], three evaluated salubrious subjects and patients with COPD or asthma [31, 46, 49], one included developed cystic fibrosis patients [47], and ane included subjects with SCI [33]. Nine studies that compared continuing or sitting positions vs. supine or RSL and LSL plant higher PEF in standing and sitting [3, 22,23,24, 31, 45,46,47,48]. 3 of vi studies comparison the standing and sitting positions constitute higher PEF in standing [46, 50, 51] and one reported higher PEF in sitting [22]. However, it is most probable that none of the differences reported in PEF are clinically significant. In SCI patients with consummate tetraplegia PEF was found to be 12% higher in the supine vs. sitting position [33].

FRC

FRC was evaluated using helium dilution in five studies [27, 41, 43, 52, 53]. Amongst good for you subjects, FRC was higher in standing [53] and in sitting [27, 43] vs. supine, with the differences reaching statistical and clinical significance. Still, the difference in sitting vs. supine was not significant among patients with obesity (hateful BMI 44–45) [41, 43] or CHF [27], and was college in sitting vs. supine in patients subsequently bariatric surgery (mean BMI 31) [41]. Another written report [52] involving subjects with mild-to-moderate obesity (hateful BMI 32), reported that FRC was significantly higher both statistically and clinically in sitting vs. supine.

Total lung capacity

2 studies that evaluated TLC using helium dilution in healthy subjects [43] and in subjects with obesity [41, 43] constitute no statistically significant difference betwixt the sitting and supine positions.

Residual volume

Ii studies that evaluated RV using helium dilution in salubrious subjects [43] and those with obesity [41, 43] found no statistically significant divergence between sitting and supine.

PEmax

Six studies investigated the association between body position and PEmax in healthy subjects [3, 28, 39, 46, 54, 55]. PEmax was higher in continuing vs. supine, in continuing vs. sitting and RSL, in sitting vs. supine [54], and in sitting vs. supine and RSL [46]; notwithstanding, the differences reported in those studies were not clinically significant. Other studies found no divergence in PEmax betwixt sitting and supine [28, 39], or between sitting, supine, RSL, and LSL [3, 55].

In COPD patients, PEmax was higher in standing or sitting vs. supine or RSL [46], and was higher in standing and sitting vs. RSL in patients with cystic fibrosis [47]. The differences were non clinically significant.

In subjects with SCI, PEmax was significantly higher in sitting vs. supine for all subjects, and for patients with motor consummate injury or incomplete cervical motor injury [37].

PImax

In good for you subjects, PImax was improved in sitting vs. supine in ii studies [three, 54]. However, other studies found no difference in PImax in sitting vs. supine [28, 39, 55], or sitting vs. RSL and LSL [3, 55]. In subjects with chronic SCI, no meaning change was seen in PImax between sitting and supine, with the exception of a subgroup of patients with consummate thoracic motor paresis where there was statistically and clinically significant comeback in sitting [37].

DLCO

Seven studies evaluated the effect of body position on diffusion capacity; six included healthy subjects [18, 20, 21, 24, 56, 57], iii included patients with CHF [18, 21, 58], and one included COPD patients [57].

Amongst healthy subjects, two studies [24, 56] found statistically and clinically pregnant improvement in DLCO in supine vs. sitting and one [57] establish a trend towards increased DLCO in supine vs. sitting, however this deviation did not reach statistical significance. One study [xviii] constitute DLCO to be higher in the sitting vs. supine positions while another study found no departure in DLCO between these positions [21]. One report [21] reported college DLCO in sitting vs. side lying while another written report [20] establish no difference between these positions. In COPD patients, no statistically significant change in DLCO was found between the sitting and the supine position [57].

Three studies investigated diffusion capacity in patients with CHF [18, 21, 58]. One report [58] constitute that postural changes from the supine to sitting positions induced different responses in diffusion capacity. In some patients diffusion capacity improved in the sitting position and others showed no modify or a decline. On the average no statistically significant difference was found between the 2 positions. The authors attributed the difference in responses to variations in pulmonary circulation pressures. Some other study [18] found no significant difference in diffusion capacity betwixt the sitting and the supine positions. Side-lying was reported to reduce DLCO in comparing to sitting in the 3rd study [21].

Discussion

Most studies in this systematic review of 43 papers evaluating the effect of torso position on pulmonary function establish that pulmonary part improved with more erect posture in both healthy subjects and those with lung disease, heart disease, neuromuscular diseases, and obesity. In patients with SCI, the outcome is more than complex and depends on the severity and level of injury. In contrast, diffusion capacity, as assessed by DLCO, increases in the supine position in healthy subjects while the issue in CHF patients is thought to depend upon pulmonary circulation force per unit area.

Decreased FVC in more recumbent positions may reflect both increased thoracic blood volume due to gravitational facilitation of venous return, which is more important in patients with heart failure, also every bit cephalic displacement of the diaphragm due to abdominal pressure in the recumbent positions, which is more than important in obese subjects [59]. In side-lying positions, fifty-fifty though merely the dependent hemi-diaphragm is displaced, the result on FVC appears to be similar to that observed in a supine position [59]. Other factors that may contribute to lower FVC values in side-lying positions include increased airway resistance and decreased lung compliance secondary to anatomical differences between the left and right lungs, as well as shifting of the mediastinal structures [20].

FEV1 was also college in cock positions. Recumbent positions limit expiratory volumes and flow, which may reflect an increase in airway resistance, a decrease in elastic recoil of the lung, or decreased mechanical reward of forced expiration, presumably affecting the large airways [20]. In asthmatic patients the increment in FVC while standing might be due to the increased diameter of the airways in this position [30].

In patients with CHF the lungs are potent and heavy, and the middle is large and heavy, increasing the negative effects of lung-heart interdependence [60]. As cardiac dimension increases, lung book, mechanical function, and diffusion capacity decrease [61, 62]; thus, the center weighs on the diaphragm while sitting and on ane of the lungs while in a side-lying position. This influences the ability of the lungs to expand laterally merely allows the diaphragm to descend and the lungs to expand inferiorly. In side-lying positions, the centre weighs on one lung, compressing both the airways and lung parenchyma, leading to a reduction in FEV1 and FVC due to airway compression [21]. Both elastic (reduced lung compliance) and resistive loads are simultaneously increased in the supine position in CHF patients [63].

Changes in FVC from the sitting to supine positions may reflect diaphragm strength/paralysis. FVC is thus an of import clinical tool for assessment of diaphragmatic weakness in patients with neuromuscular diseases [64]. In patients with ALS, supine FVC is a test of diaphragmatic weakness [65] that predicts orthopnea [25] and prognosis for survival [66, 67]. The American Academy of Neurology has ended that in ALS patients, supine FVC is probably more effective than erect FVC in detecting diaphragm weakness and correlates better with symptoms of hypoventilation [68].

In patients with cervical SCI (tetraplegia), FVC and FEV1 increase in the supine vs. sitting position. The diaphragm increases its inspiratory circuit in the supine position because its musculus fibers are longer at cease expiration, and they operate at a more effective point of their length-tension curve [69,70,71]. This mechanism is especially important in patients for whom the diaphragm is the master musculus for breathing, since their intercostal and abdominal muscles are inactive due to SCI.

FRC was reported to increase in upright positions in salubrious subjects [27, 43, 53] and in patients with mild-to-moderate obesity [41, 52]. Changing from a supine to an upright position increases FRC due to reduced pulmonary blood volume and the descent of the diaphragm. This may change the indicate in which tidal breathing occurs in the volume-pressure curve, which leads to increased lung compliance, and thus an identical pressure alter would produce a greater inspired volume if there is no alter in respiratory drive [53]. However, among patients with CHF, no deviation in FRC between sitting and supine was reported [27]. In eye failure, reduction in lung compliance in the supine position might reduce the passive change in lung volume, but FRC may be sustained above relaxation volume by an adjustment in respiratory muscle or glottal activity [27]. Among patients with obesity the sitting FRC was less than in healthy subjects but at that place was no further decrease in the supine position [43].

PEF, PEmax, and PImax were establish to increase in upright positions in salubrious subjects [iii, 23, 24, 46, 48, 50, 51] and in those with lung diseases [31, 46, 47]. This may be related to changes in lung volumes with positions.

Standing and sitting have been shown to lead to the highest lung volumes [72, 73]. At higher lung volumes the elastic recoil of the lungs and the chest wall is greater. In addition, the expiratory muscles are at a more optimal region of the length-tension bend and thus are capable of generating higher intrathoracic pressure, potentially generating college expiratory pressures and pushing air through narrow airways at loftier speed, which results in higher PEmax, PEF, and FEV1. As lung volumes decrease, muscle length becomes less optimal, which results in lower PEmax in sitting, compared to the continuing position, and even lower in more than recumbent positions. The change in PEmax influences PEF [46].

When continuing, gravity pulls the mediastinal and abdominal structures downwards, creating more space in the thoracic cavity, which allows further expansion of the lungs and greater lung volumes [74]. This, along with the subtract in pinch on the lung bases, allows alveoli to recruit and increases lung compliance. The inspiratory muscles can aggrandize fifty-fifty more, which allows the diaphragm to go along contracting downwards, thus increasing lung volumes [46].

Sitting oft leads to the somewhat reduced lung volumes compared with standing. This can be explained by several mechanisms. Outset, in sitting, abdominal organs are higher, interfering with diaphragmatic motility, thus enabling smaller inspiration. 2d, the abdominal muscles are in a less optimal betoken in the length-tension curve, since the combination of hip flexion and higher position of the intestinal contents exert upward pressure level. 3rd, the back of the chair may limit thoracic expansion. These three factors explicate a slightly lower PEmax and PEF in sitting vs. standing [46].

Diaphragmatic strength is negatively affected by the supine position, and intrathoracic blood volume is increased. These factors lead to decreased PEmax and PEF in the supine position [3].

In side-lying positions (RSL or LSL), when the bed is flat, the intestinal contents fall frontwards. The dependent hemi-diaphragm is stretched to a practiced length for tension generation, while the nondependent hemi-diaphragm is more flattened. Changes in lung volumes may thus balance themselves out due to a better diaphragmatic contraction but decreased space in the thorax [46].

The decreased PImax observed in the supine position could be related to diaphragm overload past intestinal content displacement during maximal inspiratory attempt, which could starting time improved diaphragm position on the length-tension bend. In improver, the length of all other inspiratory muscles may become less optimal in supine position [75].

In patients with cervical spinal cord injury and high tetraplegia, PEF was institute to be higher in the supine vs. sitting position [33] corresponding to the increment in FVC and FEV1 in the supine position.

In healthy subjects, most studies showed an increase in DLCO in supine vs. sitting [24, 56, 57]. This improvement is attributed to the moderate increment in alveolar blood volume in the supine position due to recruitment of lung capillary bed on transition from upright to supine. Historic period may benumb this increase [76]. This may explicate why a study that included participants with a mean historic period of 61 [21] institute no difference in DLCO between sitting and supine.

In side-lying positions, the heart weighs on one lung, compressing both airways and lung parenchyma, reducing alveolar blood volume, and causing ventilation/ perfusion mismatch. Those effects caused reduction of diffusion capacity in the side-lying positions [21].

In COPD patients, there was no change in DLCO between sitting and supine [57]. This might exist related to reduced FVC and alveolar harm in these patients. These effects might have negative touch on diffusion chapters, opposing the positive effect of the increase in blood volume in the alveoli [57].

In patients with CHF, different patterns of the consequence of posture on DLCO were observed [58]. The modify in DLCO was probably related to the change in alveolar blood volume, about likely due to differences in pulmonary artery pressure and middle dimensions [58].

Limitations of the study

At that place are a few limitations to this review. First, the level of evidence of the studies is relatively low. However, in this blazon of research, due to the nature of the populations studied and the interventions practical, it is impossible to perform a randomized control report. 2d, most studies were performed on a small number of subjects and all studies used either consecutive, convenience, or volunteer sampling. The review included merely adult subjects and it is therefore non possible to generalize the results to children and adolescents. Finally, research protocols varied between studies and detailed information nigh protocols were often missing. Patient cooperation during lung function testing strongly influences results. This may explicate contradictory results obtained in some cases. Studies that included subjects older than threescore years did not mention the cognitive office of participants, a factor that may influence patient cooperation.

Further research in this field is needed, including studies designed to evaluate lung role in a larger number of healthy participants equally well equally in individuals with a multifariousness of medical conditions. There is also a need to use a standardized protocol including randomization of postures and times betwixt tests (e.g. for wash-out of inhaled gasses or redistribution of blood volume) in different positions to enable a meliorate comparing of outcomes.

Conclusions

When performing pulmonary function tests, body position plays a role in its influence over exam results. As seen in this review, a change in body position may have varying implications depending on the patient populations. American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines [ii] recommend performing PFTs in the sitting or standing position, just the sitting position is usually preferred. The norms of those functions according to gender and historic period were established from tests performed in this position. This review suggests that for most of the subjects this is the preferred position for the exam; however, clinicians should consider performing PFTs in other positions in selected patients. In patients with SCI, testing also in the supine position may provide of import data. In patients with neuromuscular disorders, performing PFTs in the supine position may assistance to appraise diaphragmatic part.

Positioning plays an important role in maximizing respiratory function when treating patients with diverse bug and diseases and it is important to know the implications of each position on the respiratory arrangement of a specific patient. Agreement the influence of trunk position can give healthcare professionals better noesis of optimal positions for patients with different diseases.

Abbreviations

- AAN:

-

American Academy of Neurology

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DLCO:

-

Diffusing chapters of the lungs for carbon monoxide

- ERS:

-

European Respiratory Society

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in ane s

- FRC:

-

Functional rest capacity

- FVC:

-

Forced vital chapters

- LSL:

-

Left side lying

- PEF:

-

Peak expiratory flow

- PEmax:

-

Maximal expiratory pressure

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary office test

- PImax:

-

Maximal inspiratory pressure

- RSL:

-

Right side lying

- RV:

-

Residual book

- SCI:

-

Spinal cord injury

- TLC:

-

Full lung capacity

- VC:

-

Vital capacity

References

-

Crapo RO. Pulmonary-role testing. Northward Engl J Med. 1994;331(one):25–30.

-

Miller MR, Crapo R, Hankinson J, et al. General considerations for lung function testing. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(1):153–61.

-

Meysman M, Vincken Westward. Outcome of body posture on spirometric values and upper airway obstruction indices derived from the period-volume loop in immature nonobese subjects. Chest. 1998;114(4):1042–vii.

-

Pellegrino R, Viegi M, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung role tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–68.

-

Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(3):511–22.

-

Goswami R, Guleria R, Gupta AK, et al. Prevalence of diaphragmatic musculus weakness and dyspnoea in Graves' disease and their reversibility with carbimazole therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147(3):299–303.

-

Keenan SP, Alexander D, Road JD, Ryan CF, Oger J, Wilcox PG. Ventilatory muscle force and endurance in myasthenia gravis. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(vii):1130–v.

-

Nava Southward, Crotti P, Gurrieri Yard, Fracchia C, Rampulla C. Effect of a beta 2-agonist (broxaterol) on respiratory musculus force and endurance in patients with COPD with irreversible airway obstacle. Chest. 1992;101(1):133–40.

-

Quanjer PH, Lebowitz Doctor, Gregg I, Miller MR, Pedersen OF. Acme expiratory period: conclusions and recommendations of a working Party of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl. 1997;24:2s–8s.

-

Global initiative for asthma (GINA): Global strategy for asthma direction and prevention (2018 update). 2018. file:///C:/Users/owner/Downloads/wms-GINA-2018-report-V1.3–002.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1). https://doi.org/ten.1183/13993003.00016-2016.

-

Hathaway EH, Tashkin DP, Simmons MS. Intraindividual variability in serial measurements of DLCO and alveolar volume over 1 year in eight good for you subjects using three independent measuring systems. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140(6):1818–22.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;half dozen(7):e1000097.

-

Gronseth GS, Woodroffe LM, Getchuis TSD. Clinical practice guideline process manual. 2011. http://tools.aan.com/globals/axon/assets/9023.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Quality assessment tool for before-afterward (pre-postal service) studies with no control group. 2014. https://world wide web.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-cess-tools. Accessed 12 Aug 2018.

-

Kunstler Be, Cook JL, Freene Due north, et al. Physiotherapist-led physical activity interventions are efficacious at increasing physical action levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28(3):304–xv.

-

Ben-Dov I, Zlobinski R, Segel MJ, Gaides M, Shulimzon T, Zeilig Thousand. Ventilatory response to hypercapnia in C(five-8) chronic tetraplegia: the effect of posture. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(eight):1414–7.

-

Ceridon ML, Morris NR, Olson TP, Lalande S, Johnson BD. Upshot of supine posture on airway blood period and pulmonary function in stable heart failure. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;178(2):269–74.

-

Ganapathi LV, Vinoth S. The estimation of pulmonary functions in various trunk postures in normal subjects. Int J Advances Med. 2015;ii(3):250–4 http://www.ijmedicine.com/index.php/ijam/article/view/360. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Manning F, Dean E, Ross J, Abboud RT. Effects of side lying on lung function in older individuals. Phys Ther. 1999;79(5):456–66.

-

Palermo P, Cattadori G, Bussotti M, Apostolo A, Contini Thou, Agostoni P. Lateral decubitus position generates discomfort and worsens lung function in chronic heart failure. Chest. 2005;128(3):1511–6.

-

Patel AK, Thakar HM. Spirometric values in sitting, standing, and supine position. Lung Pulm Resp Res. 2015;2(1):00026 http://medcraveonline.com/JLPRR/JLPRR-02-00026.php. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Saxena J, Gupta South, Saxena S. A study of change of posture on the pulmonary function tests : tin can information technology help COPD patients? Indian J Community Health. 2006;xviii(1):10–ii. http://world wide web.iapsmupuk.org/journal/index.php/IJCH/article/view/108. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Stewart IB, Potts JE, McKenzie DC, Coutts KD. Effect of trunk position on measurements of diffusion capacity after do. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(6):440–4.

-

Varrato J, Siderowf A, Damiano P, Gregory South, Feinberg D, McCluskey Fifty. Postural alter of forced vital capacity predicts some respiratory symptoms in ALS. Neurology. 2001;57(2):357–9.

-

Vilke GM, Chan TC, Neuman T, Clausen JL. Spirometry in normal subjects in sitting, prone, and supine positions. Respir Intendance. 2000;45(four):407–10.

-

Yap JC, Moore DM, Cleland JG, Pride NB. Effect of supine posture on respiratory mechanics in chronic left ventricular failure. Am J Respir Crit Intendance Med. 2000;162(four Pt 1):1285–91.

-

Tsubaki A, Deguchi S, Yoneda Y. Influence of posture on respiratory role and respiratory musculus strength in normal subjects. J Phys Ther Sci. 2009;21(1):71–4 https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/commodity/jpts/21/ane/21_1_71/_article. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

De S. Comparison of spirometric values in sitting versus standing position among patients with obstructive lung function. Indian J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;26(2):86–eight http://medind.nic.in/iac/t12/i2/iact12i2p86.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Melam GR, Buragadda South, Alhusaini A, Alghamdi MA, Alghamdi MS, Kaushal P. Effect of different positions on FVC and FEV1 measurements of asthmatic patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(iv):591–3.

-

Mohammed J, Abdulateef A, Shittu A, Sumaila FG. Effect of unlike torso positioning on lung function variables among patients with bronchial asthma. Arch Physiother Global Res. 2017;21(3):7–12. http://apgr.wssp.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/APGR-21-3-A.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Razi E, Moosavi GA. The effect of positions on spirometric values in obese asthmatic patients. Islamic republic of iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;vi(3):151–4.

-

Linn WS, Adkins RH, Gong H Jr, Waters RL. Pulmonary function in chronic spinal cord injury: a cantankerous-sectional survey of 222 southern California adult outpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(half dozen):757–63.

-

Park JH, Kang SW, Lee SC, Choi WA, Kim DH. How respiratory muscle force correlates with coughing capacity in patients with respiratory muscle weakness. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(three):392–seven.

-

Baydur A, Adkins RH, Milic-Emili J. Lung mechanics in individuals with spinal cord injury: effects of injury level and posture. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90(two):405–11.

-

Kim M-1000, Hwangbo Grand. The effect of position on measured lung function in patients with spinal cord injury. J Concrete Therapy Sci. 2012;24(8):655–7 https://world wide web.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpts/24/8/24_JPTS-2012-029/_article. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Terson de Paleville DG, Sayenko DG, Aslan SC, Folz RJ, McKay WB, Ovechkin AV. Respiratory motor part in seated and supine positions in individuals with chronic spinal string injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;203:ix–14.

-

Poussel Yard, Kaminsky P, Renaud P, Laroppe J, Pruna L, Chenuel B. Supine changes in lung role correlate with chronic respiratory failure in myotonic dystrophy patients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;193:43–51.

-

Naitoh Southward, Tomita K, Sakai K, Yamasaki A, Kawasaki Y, Shimizu E. The effect of body position on pulmonary function, breast wall motion, and discomfort in young good for you participants. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(9):719–25.

-

Miccinilli Due south, Morrone Yard, Bastianini F, et al. Optoelectronic plethysmography to evaluate the consequence of posture on breathing kinematics in spinal cord injury: a cantankerous sectional study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52(1):36–47.

-

Sebbane M, El Kamel M, Millot A, et al. Effect of weight loss on postural changes in pulmonary function in obese dubjects: a longitudinal study. Respir Care. 2015;60(7):992–ix.

-

Myint WW, Htay MNN, Soe HHK, et al. Effect of body positions on lungs volume in asthmatic patients: a cross-sectinal study. J Adv Med Pharma Sci. 2017;13(4):i–six http://www.journalrepository.org/media/journals/JAMPS_36/2017/Jun/Myint1342017JAMPS33901.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Watson RA, Pride NB. Postural changes in lung volumes and respiratory resistance in subjects with obesity. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;98(ii):512–seven.

-

Roychowdhury P, Pramanik T, Prajapati R, Pandit R, Singh S. In wellness--vital chapters is maximum in supine position. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;thirteen(2):131–2.

-

Antunes BO, de Souza HC, Gianinis HH, Passarelli-Amaro RC, Tambascio J, Gastaldi AC. Superlative expiratory flow in healthy, young, non-active subjects in seated, supine, and prone postures. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32(6):489–93.

-

Badr C, Elkins MR, Ellis ER. The upshot of body position on maximal expiratory pressure level and catamenia. Aust J Physiother. 2002;48(2):95–102.

-

Elkins MR, Alison JA, Cheerio PT. Effect of trunk position on maximal expiratory force per unit area and menstruation in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;xl(five):385–91.

-

Gianinis HH, Antunes BO, Passarelli RC, Souza HC, Gastaldi AC. Effects of dorsal and lateral decubitus on elevation expiratory flow in healthy subjects. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17(five):435–41.

-

McCoy EK, Thomas JL, Sowell RS, et al. An evaluation of peak expiratory menses monitoring: a comparison of sitting versus standing measurements. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(two):166–seventy.

-

Ottaviano G, Scadding GK, Iacono V, Scarpa B, Martini A, Lund VJ. Peak nasal inspiratory flow and peak expiratory flow. Upright and sitting values in an adult population. Rhinology. 2016;54(2):160–iii.

-

Wallace JL, George CM, Tolley EA, et al. Peak expiratory flow in bed? A comparing of iii positions. Respir Care. 2013;58(3):494–7.

-

Benedik PS, Baun MM, Keus L, et al. Effects of body position on resting lung book in overweight and mildly to moderately obese subjects. Respir Care. 2009;54(3):334–9.

-

Chang AT, Boots RJ, Brownish MG, Paratz JD, Hodges PW. Ventilatory changes following head-up tilt and standing in healthy subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;95(5–6):409–17.

-

Costa R, Almeida Due north, Ribeiro F. Torso position influences the maximum inspiratory and expiratory rima oris pressures of young healthy subjects. Physiotherapy. 2015;101(2):239–41.

-

Ogiwara S, Miyachi T. Outcome of posture on ventilatory muscle strength. J Phys Ther Sci. 2002;xiv(one):1–5. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpts/xiv/ane/14_1_1/_pdf/-char/en. Accessed 29 May 2018.

-

Peces-Barba Chiliad, Rodriguez-Nieto MJ, Verbanck Southward, Paiva 1000, Gonzalez-Mangado N. Lower pulmonary diffusing chapters in the decumbent vs. supine posture. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004;96(5):1937–42.

-

Terzano C, Conti V, Petroianni A, Ceccarelli D, De Vito C, Villari P. Result of postural variations on carbon monoxide diffusing capacity in good for you subjects and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary affliction. Respiration. 2009;77(1):51–7.

-

Faggiano P, D'Aloia A, Simoni P, et al. Furnishings of body position on the carbon monoxide diffusing chapters in patients with chronic heart failure: relation to hemodynamic changes. Cardiology. 1998;89(ane):i–7.

-

Behrakis PK, Baydur A, Jaeger MJ, Milic-Emili J. Lung mechanics in sitting and horizontal body positions. Chest. 1983;83(4):643–6.

-

Agostoni PG, Marenzi GC, Sganzerla P, et al. Lung-middle interaction as a substrate for the improvement in exercise capacity after body fluid volume depletion in moderate congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(11):793–viii.

-

Agostoni PG, Cattadori G, Guazzi G, Palermo P, Bussotti Thou, Marenzi G. Cardiomegaly every bit a possible crusade of lung dysfunction in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2000;140(five):e24.

-

Hosenpud JD, Stibolt TA, Atwal G, Shelley D. Abnormal pulmonary function specifically related to congestive heart failure: comparison of patients before and later on cardiac transplantation. Am J Med. 1990;88(five):493–6.

-

Nava S, Larovere MT, Fanfulla F, Navalesi P, Delmastro M, Mortara A. Orthopnea and inspiratory endeavor in chronic heart failure patients. Respir Med. 2003;97(half dozen):647–53.

-

Fromageot C, Lofaso F, Annane D, et al. Supine autumn in lung volumes in the assessment of diaphragmatic weakness in neuromuscular disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(one):123–eight.

-

Lechtzin Due north, Wiener CM, Shade DM, Clawson Fifty, Diette GB. Spirometry in the supine position improves the detection of diaphragmatic weakness in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Chest. 2002;121(two):436–42.

-

Baumann F, Henderson RD, Morrison SC, et al. Use of respiratory function tests to predict survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;xi(i–2):194–202.

-

Schmidt EP, Drachman DB, Wiener CM, Clawson L, Kimball R, Lechtzin N. Pulmonary predictors of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: use in clinical trial design. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33(1):127–32.

-

Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice parameter update: the intendance of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an bear witness-based review): report of the quality standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73(xv):1218–26.

-

Fugl-Meyer AR. Furnishings of respiratory musculus paralysis in tetraplegic and paraplegic patients. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1971;3(4):141–fifty.

-

Fugl-Meyer AR, Grimby Grand. Respiration in tetraplegia and in hemiplegia: a review. Int Rehabil Med. 1984;half dozen(4):186–90.

-

Huldtgren AC, Fugl-Meyer AR, Jonasson Due east, Bake B. Ventilatory dysfunction and respiratory rehabilitation in post-traumatic quadriplegia. Eur J Respir Dis. 1980;61(vi):347–56.

-

Wade OL, Gilson JC. The effect of posture on diaphragmatic movement and vital capacity in normal subjects with a note on spirometry as an help in determining radiological chest volumes. Thorax. 1951;6(two):103–26.

-

Moreno F, Lyons HA. Effect of trunk posture on lung volumes. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:27–9.

-

Castile R, Mead J, Jackson A, Wohl ME, Stokes D. Effects of posture on period-book curve configuration in normal humans. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982;53(5):1175–83.

-

Segizbaeva MO, Pogodin MA, Aleksandrova NP. Effects of trunk positions on respiratory muscle activation during maximal inspiratory maneuvers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;756:355–63.

-

Chang SC, Chang Howdy, Liu SY, Shiao GM, Perng RP. Effects of body position and age on membrane diffusing capacity and pulmonary capillary blood volume. Chest. 1992;102(i):139–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Prof. Ora Paltiel, a specialist in Internal Medicine, Hematology, and Oncology who likewise holds a doctorate in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, for her invaluable assistance in selecting the optimal tools for assessment of the quality of evidence and potential for bias of studies included in this systematic review.

The authors wish to give thanks Shifra Fraifeld, a medical centre-based medical author and editor, for her editorial contribution during manuscript preparation.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

SK, E-LM, NA, AR contributed to the study concept and blueprint. SK, E-LM, NA, AR, YZ contributed to information conquering and analysis, and estimation of the data. The principal literature search was conducted past SK and Eastward-LM. SK and E-LM drafted the manuscript. SK, Due east-LM, NA, AR, YZ critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript prior to submission and all have responsibility for the integrity of the research process and findings. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable – systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file ane:

Table S1. Scoring for papers included in the systematic review based on the Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Mail service) Studies with No Control Group of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [3, 15,16,17,18,nineteen,twenty,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. (DOCX 63 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Statistically significant differences in pulmonary office betwixt the diverse body positions [3, 17,18,xix,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, thirty, 31, 33, 34, 37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46,47,48, 50,51,52,53,54, 56]. (DOCX 104 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Katz, Southward., Arish, N., Rokach, A. et al. The effect of body position on pulmonary office: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med eighteen, 159 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0723-4

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0723-4

Keywords

- Body position

- Lung volume

- Physical therapy

- Positioning

- Posture

- Pulmonary function

- Sitting

- Supine

- Continuing

If The Lungs Would Be Opened Out And Laid Flat, What Size Area Would They Cover?,

Source: https://bmcpulmmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12890-018-0723-4

Posted by: shellinglind.blogspot.com

0 Response to "If The Lungs Would Be Opened Out And Laid Flat, What Size Area Would They Cover?"

Post a Comment